Update on Overleaf.

This commit is contained in:

parent

71cb77b301

commit

a3db57d042

3 changed files with 222 additions and 144 deletions

BIN

Contractible loops.png

Normal file

BIN

Contractible loops.png

Normal file

Binary file not shown.

|

After

(image error) Size: 20 KiB |

305

main.tex

305

main.tex

|

|

@ -4,7 +4,7 @@

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

\usepackage[utf8]{inputenc} % Unicode source support

|

||||

\usepackage{graphicx} % Required for inserting images

|

||||

\usepackage{graphicx, caption} % Required for inserting images

|

||||

\usepackage{amsmath}

|

||||

\usepackage{amsthm}

|

||||

\usepackage{float}

|

||||

|

|

@ -15,13 +15,14 @@

|

|||

\usepackage{multicol}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\theoremstyle{definition}

|

||||

\newtheorem{definition}{Definition}[section]

|

||||

|

||||

%\usepackage[backend=biber,style=apa]{biblatex}

|

||||

|

||||

%, citestyle=apa, sorting=ynt

|

||||

\usepackage[colorlinks=true,citecolor=black, urlcolor=blue

|

||||

\usepackage[colorlinks=true,citecolor=black, urlcolor=black

|

||||

]{hyperref}

|

||||

\usepackage{verbatim}

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -30,6 +31,7 @@

|

|||

\DeclareMathOperator{\so}{SO}

|

||||

\DeclareMathOperator{\divergence}{div}

|

||||

\DeclareMathOperator{\lensop}{L}

|

||||

\DeclareMathOperator{\rotmat}{R}

|

||||

\newcommand*{\lens}[2]{\lensop\left(#1,#2\right)} %

|

||||

% \DeclareUnicodeCharacter{2254}{\coloneq} % ≔

|

||||

\renewcommand{\S}{\mathbb{S}}

|

||||

|

|

@ -48,35 +50,61 @@

|

|||

spaces} \\\ Preparation Bachelor's Project}

|

||||

|

||||

\author{Javier Gustavo Vela Castro \footnote{\href{mailto:j.g.vela.castro@student.rug.nl}{j.g.vela.castro@student.rug.nl

|

||||

}}, Adriel Matei \footnote{\href{mailto:a.r.matei@student.rug.nl}{a.r.matei@student.rug.nl}}

|

||||

, Juš Kocutar\footnote{\href{mailto:j.kocutar@student.rug.nl}{j.kocutar@student.rug.nl}}, Béla Schneider \footnote{\href{mailto:b.g.schneider@student.rug.nl}{b.g.schneider@student.rug.nl

|

||||

}}, Adriel Matei \footnote{\href{mailto:a.r.matei@student.rug.nl}{a.r.matei@student.rug.nl}},

|

||||

Juš Kocutar\footnote{\href{mailto:j.kocutar@student.rug.nl}{j.kocutar@student.rug.nl}}, Béla Schneider \footnote{\href{mailto:b.g.schneider@student.rug.nl}{b.g.schneider@student.rug.nl

|

||||

}}}

|

||||

|

||||

\date{28th February 2025}

|

||||

|

||||

\date{}

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{document}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\maketitle

|

||||

|

||||

\newpage

|

||||

\section{Abstract}

|

||||

\begin{abstract}

|

||||

|

||||

The study of temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) gives a way to understand the possible topology of the universe. In this paper, we study how assuming that the universe has a finite \textbf{spherical topology}, can constrain the possible allowed temperaturfe fluctuations of the CMB, resulting in distinct theoretical predictions for the temperature \textbf{anisotropies}. We begin by introducing a foundation for analyzing spherical 3-manifolds, focusing on \textbf{spectral geometry}, \textbf{eigenmode analysis}, and the \textbf{Laplace-Beltrami operator} to describe these temperature fluctuations.

|

||||

Then, following the results from the existing literature, we take a look at how different specific quotient spaces of the 3-sphere—such as \textbf{lens spaces} and \textbf{isospectral but non-isometric manifolds}— restrict the allowed eigenmodes of the CMB fluctuations. Next, we study the implications of {inhomogeneous spherical spaces}, where CMB fluctuations depend on observer location. Finally, to verify the viability of alternative cosmological models, we analyze \textbf{statistical tests for CMB} temperature fluctuations in harmonic space using real data from missions such as the WMAP.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\newpage

|

||||

\section*{Cover letter}

|

||||

|

||||

Suggestions we implemented:

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{enumerate}

|

||||

\item We changed the order in which we introduce the concepts such as the quotients of the sphere and the Laplace-Beltrami operator. They are now introduced at the beginning of the article, instead of multiple times throughout the text.

|

||||

\item We modified the tone of the abstract to be more formal and put it on a separate page.

|

||||

\item We changed section 4.3 to be more cohesive and have an actual conclusion, instead of ending abruptly.

|

||||

\item We fixed a multitude of typos and grammatical errors.

|

||||

\item We removed unnecessary usage of parentheses.

|

||||

\item We removed a paragraph that appeared twice.

|

||||

\item We added an explanation of what eigenmodes are.

|

||||

\end{enumerate}

|

||||

|

||||

Suggestions we did not (completely) implement: \begin{enumerate}

|

||||

\item Some referee reports have pointed out that the lack of an explanation / motivation for specific physics formulae, formulae that weren't covered in earlier courses that are part of our bachelor program. We agree that such formulae should be explained, but detailed explanations and derivations of every formula used would force us to exceed the word limit substantially, obscuring the main ideas, thus being unfeasible.

|

||||

\end{enumerate}

|

||||

|

||||

\newpage

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

We present a study of cosmic microwave background (CMB) temperature fluctuations in spherical spaces, which are the models of the universe where the space is a 3-dimensional sphere or its quotient. We give an overview of the preliminary machinery used in the study of CMB temperature fluctuations for spherical space. Next, we examine the behavior of isospectral but not isometric spherical forms. Finally, we explore the problem of testing for anisotropies in the mean of CMB temperature fluctuations for spherical spaces.

|

||||

|

||||

\newpage

|

||||

\section{Introduction}

|

||||

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the electromagnetic radiation left from the Big Bang. Temperature fluctuations provide an idea of the early state of the universe, as well as possible hints on its current shape. Observations of space missions such as COBE, WMAP and PLANK have revealed an unexpectedly low variance in CMB anisotropies, which are small variations in the radiation, at really large angular scales \cite{aurich_2012}. This goes against the expected results of the infinite and flat universe from the standard $\Lambda$CDM model.

|

||||

The \textit{cosmic microwave background} (CMB) is the electromagnetic radiation left from the Big Bang. Temperature fluctuations provide an idea of the early state of the universe, as well as possible hints on its current shape. Observations of space missions such as COBE, WMAP and PLANK have revealed an unexpectedly low variance in \textit{CMB anisotropies}, which are small variations in the radiation, at very large angular scales. Angular scale refers to the measure of separation between points on the celestial sphere, typically expressed in degrees or radians. Low variance in anisotropies goes against the expected results of the infinite and flat universe from the current standard model of the universe, i.e. the \textit{Lambda Cold Dark Matter model} ($\Lambda$CDM model).

|

||||

|

||||

This motivates exploring cosmological models beyond the infinite flat spaces. One possible explanation is that the universe is not infinite, as often assumed, but finite and multiconnected, the latter means it is connected but not simply connected. Specifically, if we consider the universe to be a finite spherical space (positively curved and closed, rather than infinite and flat), this would naturally introduce an upper limit to the size of CMB fluctuations \cite{aurich_2012}, potentially explaining lower large-angle correlations.

|

||||

This motivates exploring cosmological models beyond infinite flat spaces. One possible explanation is that the universe is not infinite, as often assumed, but finite and multiconnected, that is connected but not simply connected. Specifically, considering the universe to be a finite spherical space (positively curved and closed, rather than infinite and flat) would naturally introduce an upper limit to the size of CMB fluctuations \cite{aurich_2012}\cite{aurich_2005}, potentially explaining lower correlations at large angular scales.

|

||||

|

||||

The spherical space topology has been studied as a candidate for the shape of the universe by many researchers. For example, the 3-sphere $\mathbb{S}^3$ and its quotient manifolds can produce lower CMB power on large scales due to their finite size \cite{aurich_2012}. Some authors systematically examined entire families of spherical topologies such as lens spaces $L(p,q) = \mathbb{S}^3/Z_p$ (taking the quotient of $\mathbb{S}^3$ by the group of rotations of order $p$) with $p\le 500$ being the upper bound \cite{aurich_2012}. While such models did not show a dramatically strong suppression of CMB power in the tested range, they set an important methodology for how one might analyze and compare CMB temperature fluctuations in spherical space models. The important component of the articles involved is how these theoretical results compare to observations and what do they imply about the possible (shape) topology of the universe.

|

||||

The spherical space topology has been studied as a candidate for the shape of the universe by many researchers. For example, the 3-sphere $\mathbb{S}^3$ and its quotient manifolds can produce lower CMB power on large scales due to their finite size \cite{aurich_2005}. Various studies have systematically examined families of spherical topologies, such as lens spaces $\mathbb{S}^3/Z_p$, where the quotient of $\mathbb{S}^3$ is taken by the group of rotations of order $p$, with $p\le 500$ being a typical upper bound \cite{aurich_2012}. While such models did not show a dramatically strong suppression of CMB power in the tested range, they set an important methodology for how one might analyze and compare CMB temperature fluctuations in spherical space models. The important component of the articles involved is how these theoretical results compare to observations and what are the implications of these findings regarding the possible topology (i.e. shape) of the universe.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\section{Preliminaries}

|

||||

\subsection{Manifolds}

|

||||

Metric and topological spaces allow us to generalize concepts from analysis like limits, sequences, and continuity. As a reminder, metric spaces generalize distance and topological spaces generalize open sets, which can both be used to redefine all these other concepts from analysis. This is useful, as it allows those concepts to be used in completely different settings.

|

||||

Metric and topological spaces allow us to generalize concepts from analysis, including limits, sequences, and continuity. As a reminder, metric spaces generalize distance and topological spaces generalize neighborhoods, which can both be used to reconstruct the concepts from analysis. This is useful, as it allows those concepts to be used in novel settings.

|

||||

|

||||

The definition of a topological space is too general to meaningfully describe physical reality. The concept of topological manifolds tries to limit the potential pathological examples of topological spaces by requiring the spaces to look Euclidean at a local level. Formally, this means that any point on the set has a neighborhood around it equivalent (homeomorphic) to an open set of Euclidean space.

|

||||

The definition of a topological space is too general to meaningfully describe physical reality. The concept of topological manifolds tries to limit the potential pathological examples of topological spaces by requiring the spaces to look Euclidean at the local level. Formally, this means that any point on the set has a neighborhood that is equivalent (homeomorphic) to an open set of Euclidean space.

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{figure}[h]

|

||||

\centering

|

||||

|

|

@ -85,19 +113,19 @@ The definition of a topological space is too general to meaningfully describe ph

|

|||

\label{fig:mug-neighbourhoods}

|

||||

\end{figure}

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{definition}

|

||||

A topological space $M$ is a \textbf{topological manifold} of dimension $n$, or topological $n$-manifold, if it has the following properties:

|

||||

\begin{definition}[\textbf{Topological manifold}]

|

||||

A topological space $M$ is a topological manifold of dimension $n$, or topological $n$-manifold, if it has the following properties:

|

||||

\begin{itemize}

|

||||

\item $M$ is a Hausdorff space,

|

||||

\item $M$ is second countable,

|

||||

\item $M$ is locally euclidean of dimension $n$, that is, for any point $p \in M$ there exist an open subset $U \subset M$ with $p \in U$, and open subset $V \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ and a homeomorphism $\varphi: U \rightarrow V$.

|

||||

\item $M$ is locally euclidean of dimension $n$, that is, for any point $p \in M$ there exists an open subset $U \subset M$, a point $p \in U$, and an open subset $V \subset \mathbb{R}^n$ together with a homeomorphism $\varphi: U \rightarrow V$.

|

||||

\end{itemize}

|

||||

\end{definition}

|

||||

|

||||

Where second-countability is defined as follows.

|

||||

We recall that second-countability is defined as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{definition}[]

|

||||

A topological space $(X,T)$ is said to be \textbf{second countable} if there exists a countable set $B \subset T$ such that any open set can be written as a union of sets from $B$. In such case, $B$ is called a (countable) basis for the topology $T$ .

|

||||

\begin{definition}[\textbf{second countable}]

|

||||

A topological space $(X,\mathcal T)$ is said to be second countable if there exists a countable set $B \subset \mathcal T$ such that any open set can be written as a union of sets from $B$. In such case, $B$ is called a (countable) basis for the topology $\mathcal T$ .

|

||||

\end{definition}

|

||||

|

||||

%This is very useful, as it allows us to `pull back' many familiar concepts from Euclidean space (for instance, derivatives). Still, this turns out not to be enough. Analysis is built upon limits and sequences, yet those building blocks can behave in unexpected ways when taken out of the Euclidean setting.

|

||||

|

|

@ -105,41 +133,49 @@ Where second-countability is defined as follows.

|

|||

For one, limits need not be unique in the general case. This could happen if there are not enough neighborhoods to direct the sequence to a single point, which is why we require manifolds to be Hausdorff.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Moreover, sequences are just functions from the naturals to our space, so they are inherently `countable' in nature. Indeed, we are used to many nice properties of limits. For instance, if a function in real space preserves the limits of sequences, then it is guaranteed to be continuous. But such a test might not hold in the general case. Indeed, there could be too many neighborhoods around each point, such that a simple sequence does not suffice for detecting properties like continuity. Requiring the space to be first countable (that is, requiring that each point has a countable basis for its neighborhoods) solves this issue. In fact, we require an even stronger condition for manifolds in second countability (that is, a countable basis must exist for the entire space). %%I'm actually not super sure what second countability adds over first countability here, but perhaps even first countability can have the issue of ``too many open sets'' (this time at a global level).

|

||||

Moreover, sequences are just functions from the naturals to our space, so they are inherently \emph{countable} in nature. Indeed, we are used to many nice properties of limits. For instance, if a function in real space preserves the limits of sequences, then it is guaranteed to be continuous. But such a test might not hold in the general case. Indeed, we could find too many neighborhoods around each point, such that a simple sequence does not suffice for detecting properties like continuity. Requiring the space to be \emph{first countable} (that is, requiring that each point has a countable basis for its neighborhoods) solves this issue. In fact, we require an even stronger condition for manifolds in second countability (that is, a countable basis must exist for the entire space). %%I'm actually not super sure what second countability adds over first countability here, but perhaps even first countability can have the issue of ``too many open sets'' (this time at a global level).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

For a more in-depth treatment of manifolds and their manifold properties, the reader should consider \cite{serri}. A more thorough exposition of the way limits and sequences break down in the general setting (and how we can work around that) can be found in the third chapter of \cite{topcat}.

|

||||

For a more in-depth treatment of manifolds and their many-fold properties, the reader should consider \cite{serri}. A more thorough exposition of the way limits and sequences break down in the general setting (and how we can work around that) can be found in the third chapter of \cite{topcat}.

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{Curvature and holes}

|

||||

|

||||

When transporting (i.e. moving) a vector around a loop on a flat plane, the vector will arrive at the starting point in the same orientation it left as. This turns out not to be the case in the more general setting. We can quantify the amount by which this fails around every point using the concept of Gaussian curvature. Intuitively, when the curvature is $0$, the space is flat (at a point). When the curvature is positive, the space is convex (around said point), giving rise to spherical geometry. Otherwise, the space is hyperbolic (around the point). For larger dimensions, the Riemann curvature tensor allows us to take the Gaussian curvature along different slices formed by different sections.

|

||||

|

||||

A natural application of the above is detecting the curvature of the universe itself, i.e. the nature of the (spatial) geometry in which we exist. Our best tool when it comes to trying to detect such matters is the study of the cosmic microwave background radiation. In particular, this article is interested in the consequences of assuming that the underlying geometry is spherical. Indeed, although this might sound trivial (i.e. the universe would spatially be the surface of a giant four-dimensional ball), more interesting spaces arise when we allow the underlying space to have `holes'.

|

||||

A natural application of the above is detecting the curvature of the universe itself, i.e. the nature of the (spatial) geometry in which we exist. Our best tool when it comes to trying to detect such matters is the study of the cosmic microwave background radiation. In particular, this article is interested in the consequences of assuming that the underlying geometry is spherical. Indeed, although this might sound trivial (i.e. the universe would spatially be the surface of a giant four-dimensional ball), more interesting spaces arise when we allow the underlying space to have \emph{holes}.

|

||||

|

||||

Topologically, holes can be detected using homology groups (the abelian group of loops in the space, under the identification of loops that can be smoothly transformed into each other as equivalent). In particular, a space is contractible if any loop can be smoothly transformed into the trivial loop (a path that never leaves the initial point). That is, the (first) homology group must be trivial. We say a space is simply connected when it is both contractible and path connected (i.e. every two points are connected by a path).

|

||||

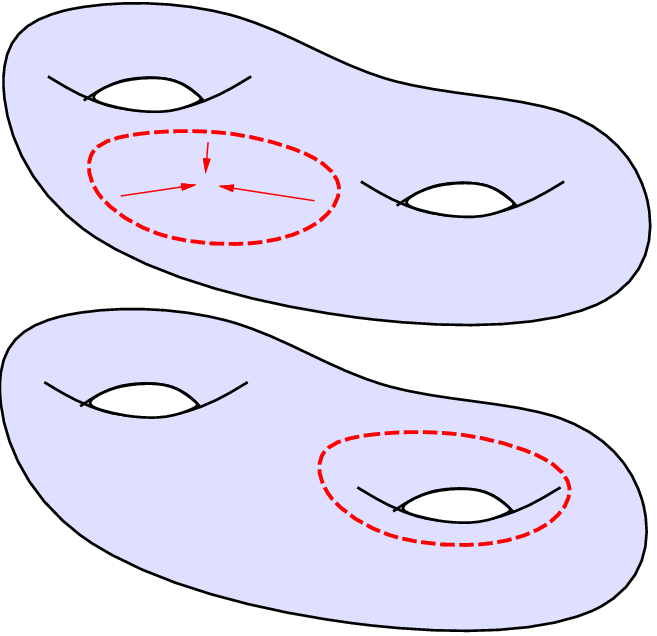

Topologically, holes can be detected using homotopy groups (the group of loops in the space, under the identification of loops that can be smoothly transformed into each other as equivalent). In particular, a space is contractible if any loop can be smoothly transformed into the trivial loop (a path that never leaves the initial point). That is, the (first) homology group must be trivial. We say a space is simply connected when it is both contractible and path connected (i.e. every two points are connected by a path).

|

||||

|

||||

%\begin{figure}[H]

|

||||

% \centering

|

||||

% \includegraphics[width=0.25\linewidth]{amogus.png}

|

||||

% \caption{The yellow path is not contractible in the space highlighted in red (there's an additional hole in the back of the figure, thus the path cannot simply contract through there)}

|

||||

% \label{fig:amogus}

|

||||

%\end{figure}

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{figure}[H]

|

||||

\centering

|

||||

\includegraphics[width=0.25\linewidth]{amogus.png}

|

||||

\caption{The yellow path is non contractible on the space highlighted in red (there's an additional hole in the back of the figure, thus the path cannot simply contract through there)}

|

||||

\label{fig:amogus}

|

||||

\captionsetup{width=.75\linewidth}

|

||||

\includegraphics[width=0.25\linewidth]{Contractible loops.png}

|

||||

\caption{Diagram showing two double tori. The red dotted path on the top double torus is a contractible loop, while the red path on the bottom one is not contractible. \cite{Herlihy_1996}}

|

||||

\label{fig:CoLoop}

|

||||

\end{figure}

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{Quotients of the $3$-sphere}

|

||||

|

||||

In what follows we use the concrete definition of the 3-sphere as an embedded submanifold of $\mathbb{R}^4$ lying in Euclidean space meaning $\mathbb{S}^3 := \{x \in \mathbb{R}^4 \; |\; \|x\| = 1\}.$ Next we define a certain special set of matrices which induce well-defined maps on the sphere.

|

||||

In what follows, we use the concrete definition of the 3-sphere as an embedded submanifold of $\mathbb{R}^4$ lying in Euclidean space, namely $\mathbb{S}^3 \coloneq \{x \in \mathbb{R}^4 \; |\; \|x\| = 1\}.$ Next we define a special set of matrices which induces well-defined maps on the sphere.

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{definition}

|

||||

We define $$SO(4) = \{A \in \mathbb{R}^{4 \times 4}:\; A^TA = I_4, \; \det(A) = 1\}.$$

|

||||

We define $$SO(4) \coloneq \{A \in \mathbb{R}^{4 \times 4}:\; A^TA = I_4, \; \det(A) = 1\}.$$

|

||||

\end{definition}

|

||||

|

||||

By the standard action of $\mathbb{R}^{4 \times 4} $ on $\mathbb{R}^4$ we have that $SO(4)$ is naturally a subgroup of the group of isometries of $\mathbb{S}^3$. This is because for any $x \in \mathbb{S}^3$ we get $$\|Ax\| = (Ax)^T(Ax) =

|

||||

By the standard action of $\mathbb{R}^{4 \times 4} $ on $\mathbb{R}^4$, we identify $SO(4)$ naturally as a subgroup of the isometry group of $\mathbb{S}^3$. This is because for any $x \in \mathbb{S}^3$ we get $$\|Ax\| = (Ax)^T(Ax) =

|

||||

x^T(A^TA)x = x^Tx = \|x\| =1$$

|

||||

hence $Ax \in \mathbb{S}^3$ implying $A|_{\mathbb{S}^3}$ is a well-defined map and a bijection. By analogous reasoning, we find that:

|

||||

|

||||

hence $Ax \in \mathbb{S}^3$ implying $A|_{\mathbb{S}^3}$ is a well-defined map and a bijection. By analogous reasoning, we find that

|

||||

$$\|Ax - Ay\| = \|A(x-y)\| = \|x-y\|,$$ hence $A$ is an isometry.

|

||||

|

||||

Next, for any subgroup $H \leq SO(4)$ we can consider the orbits of the action of $H$ on $\mathbb{S}^3$. We recall from group theory that this produces an equivalence relation on $\mathbb{S}^3$ where $x \sim y$ whenever $x$ and $y$ are in the same orbit of $H$. That is, the set of equivalency classes of $\mathbb S^3$ with

|

||||

$$x \sim y \,\iff\, \exists\, g\in H: x = g\cdot y.$$

|

||||

|

||||

The set $\mathbb{S}^3/_\sim$ can be given a manifold structure if certain conditions on the projection $\pi: \mathbb{S}^3 \to\mathbb{S}^3 /_\sim $ are satisfied, the details can be found in \cite{serri}. For instance, if $H$ is a finite subgroup of $SO(4)$ then the manifold $\mathbb{S}^3 /_\sim$ is a 3-manifold which has positive curvature, similar to $\mathbb{S}^3$.

|

||||

Next, for any subgroup $\Gamma \leq SO(4)$ we can consider the orbits of the action of $\Gamma$ on $\mathbb{S}^3$. We recall from group theory that this produces an equivalence relation on $\mathbb{S}^3$, where $x \sim y$ precisely when $x$ and $y$ are in the same orbit of $\Gamma$. That is, the set of equivalency classes of $\mathbb S^3$ with

|

||||

$$x \sim y \,\iff\, \exists\, g\in \Gamma: x = g\cdot y.$$

|

||||

The set $\mathbb{S}^3/_\sim$ can be given a manifold structure if certain conditions on the projection $\pi: \mathbb{S}^3 \to\mathbb{S}^3 /_\sim $ are satisfied, the details of which can be found in \cite{serri}. For instance, if $\Gamma$ is a finite subgroup of $SO(4)$ then the manifold $\mathbb{S}^3 /_\sim$ is a 3-manifold with positive curvature, similarly to $\mathbb{S}^3$ itself (which can be constructed when starting with the trivial group).

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{comment}

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -162,40 +198,41 @@ There is an alternative way of viewing the quotient $\mathbb{S}^3/\Gamma$ using

|

|||

|

||||

\section{Discussion of results from selected articles}

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{The spectral geometry of hyperbolic and spherical spaces (E. A. Lauret and B. Linowitz)}

|

||||

\subsection{The spectral geometry of hyperbolic and spherical spaces}

|

||||

|

||||

In \cite{emilio}, the authors go over the theoretical grounding of the literature on the topic. The candidate manifolds for the shape of the universe are, as discussed above, manifolds of the form $\mathbb S^3 / \Gamma$ (for some subgroup $\Gamma$ of the isometry group of the sphere, i.e. $\so(4)$). We will refer to such spaces as `space forms.

|

||||

In \cite{emilio}, the authors go over the theoretical grounding of the literature on the topic. We refer to quotients $\mathbb S^n / \Gamma$, defined analogously to the $\S^3$ case for some subgroup $\Gamma$ of the isometry group of the $n$-sphere as \emph{sphere forms}.

|

||||

|

||||

An important class of manifolds are the so-called `lens spaces', which correspond to the case where $\Gamma$ is cyclic and the dimension of the underlying manifold is odd. As we are interested in studying the shape of our (spatially) three-dimensional universe, all the spaces we are interested in will be lens spaces as long as $\Gamma$ is cyclic.

|

||||

An important class of manifolds are the so-called \emph{lens spaces}, which correspond to cyclic groups $\Gamma$ with the the dimension of the underlying manifold being odd. As we are interested in studying the shape of our (spatially) three-dimensional universe, all the spaces we are interested in will be lens spaces as long as $\Gamma$ is cyclic.

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{definition}[Lens spaces]

|

||||

Formally, we denote by $\lens q s$ (where $q \in \mathbb N$, $s \in \mathbb Z ^n $ and $\gcd(q, s_i) = 1$ for all $i$), the space $\mathbb S^{2n - 1} / \Gamma _{q;s}$, where $\Gamma_{q;s}$ is the (cyclic) group generated by the diagonal matrix with diagonal entries $R(2 \pi s_i/ q)$ (where $R(-)$ is a two-dimensional rotation matrix by the given angle).

|

||||

\begin{definition}[\textbf{Lens spaces}]

|

||||

Let $q\in\mathbb N$ and $s\in\Z^n$ such that $\gcd(q,s_i)=1$ for all $i$. We then defined the lens space $\lens q s := \mathbb S^{2n - 1} / \Gamma _{q;s}$, as the space induced by $\Gamma_{q;s}$, the (cyclic) group generated by the diagonal block matrix with entries\footnote{Here we use $R(\theta)$ to denote the $2$-dimensional rotation matrix rotating by the given angle, i.e. $$\rotmat(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} \cos\theta & \sin\theta \\ -\sin\theta & \cos\theta \end{pmatrix}.$$} $\rotmat(2 \pi s_i/ q)$.

|

||||

\end{definition}

|

||||

The condition $\gcd(q, s_i) = 1$ is necessary to ensure that $\Gamma$ acts freely on $\mathbb S^{2n-1}$.

|

||||

The condition $\gcd(q, s_i) = 1$ is necessary to ensure that $\Gamma$ acts freely on $\mathbb S^{2n-1}$, i.e. for every $g\in \Gamma$ and $x \in \mathbb S^{2n-1} $ the relation $gx =x$ implies $g = \text{id}$, or in other words, the action of $g$ has no fixed points for any $g \neq \text{id}$.

|

||||

|

||||

The Laplace-Beltrami operator generalizes the Laplace operator on smooth functions defined on $\mathbb{R}^n$ to general manifolds.

|

||||

\begin{definition}[Laplace-Beltrami operator]

|

||||

The Laplace-Beltrami operator is defined as the divergence of the gradient:

|

||||

The \emph{Laplace-Beltrami operator} generalizes the Laplace operator from smooth functions defined on $\mathbb{R}^n$ to general manifolds.

|

||||

\begin{definition}[\textbf{Laplace-Beltrami operator}]

|

||||

The Laplace-Beltrami operator is defined as the divergence of the gradient

|

||||

\begin{align*}

|

||||

\Delta f \coloneqq \divergence (\nabla f)

|

||||

\Delta f \coloneqq \divergence (\nabla f).

|

||||

\end{align*}

|

||||

\end{definition}

|

||||

|

||||

In particular, the spectrum of Laphlace-Beltrami operator (collection of eigenvalues) in $L^2(M, g)$ is a discrete subset of the non-negative reals, in which every value occurs with a finite multiplicity. Two such manifolds are said to be isospectral if they share a spectrum.

|

||||

The \emph{spectrum} of the Laplace-Beltrami operator is defined as its collection of eigenvalues. We also refer to this spectrum as the spectrum of the underlying manifold. It turns out that said spectrum is a discrete subset of the non-negative reals, in which every value occurs with a finite multiplicity. Two manifolds are said to be \emph{isospectral} if they share a spectrum.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Inverse spectral geometry studies the different ways in which the spectrum affects different properties of the underlying space. For instance, the dimension and volume of a manifold are completely determined by its spectrum. However, this spectrum does not completely determine the manifold uniquely up to isometry.

|

||||

The \emph{Inverse spectral geometry} studies the different ways in which the spectrum affects different properties of the underlying space. For instance, the dimension and volume of a manifold are completely determined by its spectrum. However, the spectrum does not completely determine the manifold uniquely up to isometry.

|

||||

|

||||

\subsubsection{Volume maximizing isospectral pairs of sphere forms}

|

||||

|

||||

The first important problem tackled by \cite{emilio} is that of determining the isospectral sphere form pair (that is, a pair of spaces that are isospectral yet not isometric) of largest volume. According to \cite{ikeda80}, if $\mathbb S^{2n-1}/\Gamma_1$ and $\mathbb S^{2n-1}/\Gamma_2$ are isospectral spherical forms, the two groups have equal order and equal set of element orders. As a consequence, one is cyclic only if the other is cyclic (thus one space is a lens space if and only if the other is as well).

|

||||

The first important problem tackled by \cite{emilio} is that of determining the \textit{isospectral sphere form pair} (that is, a pair of spaces that are isospectral yet not isometric) of largest volume. According to \cite{ikeda80}, if $\mathbb S^{2n-1}/\Gamma_1$ and $\mathbb S^{2n-1}/\Gamma_2$ are isospectral spherical forms, the two groups have equal order and equal set of element orders. As a consequence, one is cyclic only precisely when the other is cyclic (thus one space is a lens space if and only if the other is as well).

|

||||

|

||||

After classifying $\Gamma$ for spherical forms with homotopy group of order strictly smaller than $24$ and non-cyclic into four specific groups of different orders (the specific groups are irrelevant here), the paper concludes that if a pair of odd-dimensional isospectral but not isometric spherical space forms exists with fundamental group of order strictly less than $24$, then the two are cyclic (otherwise one of the two would be one of the four groups classified above, but then so would the other, as by \cite{ikeda80} isospectral pairs share their cyclic-ness), and thus lens spaces. The isospectral pair with the largest volume must then also be the one containing lens spaces (since no other kind of pair can exist for such groups). The paper then defines a way to generate larger lens spaces from smaller ones by concatenating the indices (which we denoted earlier by $s$, and can be treated like ordered lists here). Together with a computational search, the paper was able to build a table of the precise lens spaces that maximize volume for multiple dimensions, although whether lens spaces are the solutions for all dimensions is still an open question.

|

||||

After classifying $\Gamma$ for spherical forms with non-cyclic homotopy group of order strictly smaller than $24$ into four specific groups of different orders (the specific groups are irrelevant here), the paper concludes that if a pair of odd-dimensional isospectral but not isometric spherical space forms exists with fundamental group of order strictly lesser than $24$, then the two are lens spaces, otherwise one of the two would be one of the four non-cyclic groups classified above, but then so would the other, as by \cite{ikeda80} isospectral pairs share their cyclic-ness. The isospectral pair with the largest volume must then also be the one containing lens spaces, since no other kind of pair can exist for such groups. The paper then defines a way to generate larger lens spaces from smaller ones by concatenating the indices, which we denoted earlier by $s$, and can be treated like ordered lists here. Together with a computational search, the paper was able to build a table containing the precise lens spaces that maximize volume for multiple dimensions, although whether lens spaces are the solutions for all dimensions is still an open question.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\subsubsection{The silver lining}

|

||||

|

||||

While the study of isospectral pairs is indeed interesting, we can take solace in knowing that no such pairs exist in dimension three. That is, for the purpose of this article, all pairs of isospectral sphere forms must also be isometric. The motivated reader is encouraged to read \cite{emilio} for further details.

|

||||

While the study of isospectral pairs is interesting in its own right, we can take solace in knowing that no such pairs exist in dimension three. That is, for the purpose of this article, all pairs of isospectral sphere forms must also be isometric. The motivated reader is encouraged to read \cite{emilio} for further details. For the rest of this paper, our primary means of CMB analysis will relate to the spectrum of different concrete models of spherical universes.

|

||||

|

||||

A key aspect of this pursuit is understanding the ways in which \emph{eigenmodes of the Helmholtz equation} (which we formally define in the next section) behave under different spherical topologies, as these modes determine the possible temperature fluctuations in a CMB model. The work of Aurich, Lustig, and Steiner (2005) explores these spectral properties and their consequences for modeling CMB fluctuations in spherical space forms.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -209,57 +246,60 @@ While the study of isospectral pairs is indeed interesting, we can take solace i

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{CMB Anisotropy of Spherical Spaces (R. Aurich, S. Lustig and F. Steiner)}

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{CMB Anisotropy of Spherical Spaces}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In \cite{aurich_2005} the authors consider the 3-manifolds of the form $\mathcal{M} := \mathbb{S}^3 /_ \sim$ where $\sim$ is an equivalence relation coming from identifying orbits of some finite subgroup of the special linear group $SO(4)$.

|

||||

In \cite{aurich_2005} the authors consider the 3-manifolds of the form $M := \mathbb{S}^3 /_ \sim$ where $\sim$ is an equivalence relation coming from identifying orbits of some finite subgroup $H$ of the special orthogonal group $SO(4)$.

|

||||

|

||||

On any smooth manifold we can define the notion of smooth functions and the Laplace-Beltrami operator $\Delta$, as explained before. One can then consider the solutions of the so-called Helmholtz equation on $\mathcal{M}$ given by

|

||||

|

||||

$$(\Delta + E_\beta^\mathcal{M})\psi_\beta^{\mathcal{M}, i} = 0$$

|

||||

where $E_\beta^\mathcal{M} \in \mathbb{R}$ the functions $\psi_\beta^{\mathcal{M}}$ is a smooth function on $\mathcal{M}$ and $\beta \in \mathbb{N}.$ We call the function $\psi_\beta^\mathcal{M}$ the eigenmode of the Helmholtz operator and $E_\beta^\mathcal{M}$ the corresponding eigenvalue.

|

||||

As explained in \cite{luminet_2005}, we can lift any eigenmode $\psi _\beta^\mathcal{M}$ of the Helmholtz equation on $\mathcal{M}$ to an $H$-invariant eigenmode

|

||||

${\psi'}_\beta^\mathcal{M}$ on $\mathbb{S}^3$, meaning it satisfies the Helmholtz equation

|

||||

and ${\psi'}_\beta^\mathcal{M}(hx) = {\psi'}_\beta^\mathcal{M}(x)$ for all $h \in H$.

|

||||

On any smooth manifold one can define the notion of smooth functions and the Laplace-Beltrami operator $\Delta$, as explained in the previous section. One can moreover consider the solutions of the so-called \textit{Helmholtz equation} on $M$ given by

|

||||

$$(\Delta + E_\beta^M)\psi_\beta^{M, i} = 0,$$

|

||||

where $E_\beta^M \in \mathbb{R}$, the function $\psi_\beta^{M}$ is a smooth function on $M$, and $\beta \in \mathbb{N}.$ We call the function $\psi_\beta^M$ the \textit{eigenmode} of the Helmholtz operator and $E_\beta^M$ the corresponding eigenvalue.

|

||||

As explained in \cite{luminet_2005}, we can lift any eigenmode $\psi _\beta^M$ of the Helmholtz equation on $M$ to an $H$-invariant eigenmode

|

||||

${\psi'}_\beta^M$ on $\mathbb{S}^3$, meaning it satisfies the Helmholtz equation

|

||||

and ${\psi'}_\beta^M(hx) = {\psi'}_\beta^M(x)$ for all $h \in H$.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

From \cite{aurich_2005} we see that, in fact, the spectrum of the Helmholtz operator is a discrete subset of $\mathbb{R}$ and that $E_\beta = \beta^2 - 1$ for $\beta \in \mathbb{N}$, we call $\beta$ a wave number. However, depending on the group $H$, not all wave numbers $\beta$ are possible.

|

||||

From \cite{aurich_2005} we know that the spectrum of the Helmholtz operator is a discrete subset of $\mathbb{R}$ and that $E_\beta = \beta^2 - 1$ for $\beta \in \mathbb{N}$. We call $\beta$ a \emph{wave number}. However, depending on the group $H$, not every natural $\beta$ is a possible wave number --- the eigenmode does not exist for some. For example:

|

||||

\begin{enumerate}

|

||||

\item If $H = \{1\}$ (the trivial group), the set of wave numbers is $\mathbb{N}$ itself without restrictions.

|

||||

\item If $H = \mathbb Z/m\mathbb Z$ for odd $m$ (that is, if the underlying manifold is a lens space), the set of wave numbers is $$\{1,3,\cdots, m\}\cup \{m+1, m+2, m+3, \cdots \}.$$

|

||||

\item If $H = O^*$, the binary tetrahedral group --- a subgroup of $SO(4)$ of size 24, the set of wave numbers turns out to be $$\{ 1,7,9 \} \cup \{13,15,17,\cdots \}.$$

|

||||

\end{enumerate}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

For instance, if $H = {1}$, the trivial group, we know that the set of wave numbers is $\mathbb{N}$ itself, i.e. no restrictions. If $H = Z_m$, i.e. the cyclic group where $m$ is an odd number we get that the set of wave numbers is $\{1,3,\cdots, m\}\cup \{m+1, m+2, m+3, \cdots \}$.

|

||||

Furthermore, we can write any eigenfunction of the Helmholtz operator on $M$ in terms of known eigenfunctions on $\mathbb{S}^3$ while being able to compute the necessary coefficients.

|

||||

|

||||

Section 3 of \cite{aurich_2005} constitutes the technical part of the paper, the complete understanding of which requires a background in cosmology. The authors' goal is to compute the relative fluctuations $\frac{\delta T}{T}$ of the CMB for the various spherical manifolds obtained as the quotients of finite subgroups of $SO(4)$. First, they explain how the CMB fluctuations arise as manifestations of different effects, such as the Sachs-Wolfe contribution. For the computations, the authors assume that the initial values for the fluctuations corresponding to each wave number are certain Gaussian random variables.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Furthermore, we can then expand any eigenfucntion of the Helmholtz operator on $\mathcal{M}$ in terms of eigenfunctions on $\mathbb{S}^3$ which are explicitly known and the authors know how to compute the coefficients.

|

||||

|

||||

Section 3 of \cite{aurich_2005} forms the technical part of their paper. The complete understanding of it also requires a certain background in cosmology. Their goal is to compute the relative fluctuations $\frac{\delta T}{T}$ of CMB for all of the spherical manifolds obtained as the quotients of finite subgroups of $SO(4)$. First, they explain how the CMB fluctuations arise as manifestations of different effects such as the Sachs-Wolfe contribution. For the calculations they assume that the initial values for the fluctuations for each wave number were certain Gaussian random variables.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

After the derivation they arrive, for each spherical manifold, the value for the angular power spectrum $\delta T^2_l$ for $l = 1,2,3$, which are certain real numbers which can be directly derived from $\delta T$ after writing

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

$$\delta T (\hat{n}) =\sum_{l \geq 2}\sum_{m = -l}^{m = l}a_{lm}\tilde{Y}(n)$$

|

||||

|

||||

in terms of spherical harmonics $\tilde{Y}_{lm}$ which comprise an orthonormal basis for $L^2(\mathbb{S}^2)$ (the two sphere $\mathbb{S}^2$ is the natural domain for the CMB when we observe it.)

|

||||

|

||||

The definition of the angular power spectrum is then

|

||||

The authors arrive, for each spherical manifold, at the value for the \emph{angular power spectrum} $\delta T^2_l$ when $l = 1,2,3$, which are real numbers that can be directly derived from $\delta T$ written as

|

||||

$$\delta T (\hat{n}) =\sum_{l \geq 2}\sum_{m = -l}^{m = l}a_{lm}\tilde{Y}_{lm}(n)$$

|

||||

in terms of $\tilde{Y}_{lm}$ which are \emph{spherical harmonics} - a certain family of smooth functions defined on $\mathbb{S}^2$ which forms an orthonormal basis for $L^2(\mathbb{S}^2)$, meaning they are orthogonal and of size 1, with respect to the $L^2$ inner product. The two sphere $\mathbb{S}^2$ is the natural domain for the CMB when we observe it from Earth.

|

||||

|

||||

The angular power spectrum is defined as

|

||||

$$\delta T^2_l = \frac{l(l+1)}{2}\frac{1}{2l+1 }\left\langle \sum_{m = -l}^la_{lm}^2\right\rangle.$$

|

||||

For each spherical manifold, the authors plot $\delta T_l^2$ with respect to $\Omega_{tot}$, together with $\delta T^2_l$ as measured in WMAP. The variable $\Omega_{tot}$ is the density parameter of the universe, and can be obtained from measurements.

|

||||

|

||||

\subsubsection{Results}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The authors conclude that the spherical manifolds which align closest with the measured data are the ones obtained when setting $H = O^*$ and $H = I^*$, the \textit{binary octahedral} and \textit{binary icosahedral} groups respectively, which are of orders $48$ and $120$. The authors present an explicit description of the groups generated by left- and right- multiplication of certain quaternions, but we will omit the details for the sake of brevity.

|

||||

|

||||

They plot, for each spherical manifold, $\delta T_l^2$ with respect to $\Omega_{tot}$. The variable $\Omega_{tot}$ is the density parameter of the universe, and can be obtained from measurements. In the same plot they also show $\delta T^2_l$ as measured in WMAP.

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{Results}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The authors conclude that the spherical manifolds which align closest with the measured data are the ones obtained when setting $H = O^*$ and $H = I^*$, the binary octahedral and binary icosahedral group respectively, which are respectively of order 48 and 120. The authors presented an explicit description of the groups generated by left- and right- multiplication of certain quaternions, but we will not go in detail here.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Furthermore, they excluded other groups such as the binary tetrahedral group $T^*$ and infinite families of binary dihedral groups and cyclic groups as possible models because they exhibited drastically different behavior.

|

||||

Furthermore, the authors excluded other groups (such as the binary tetrahedral group $T^*$ and infinite families of binary dihedral groups and cyclic groups) as possible models of the universe, as they exhibit drastically different behavior.

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{figure}[H]

|

||||

\centering

|

||||

\includegraphics[width=0.25\linewidth]{binary-octahedron.png}

|

||||

\caption{Graphical representation of the binary tetrahedral group

|

||||

\cite{Egan_2021}}

|

||||

\label{fig:binary-octahedron}

|

||||

\end{figure}

|

||||

|

||||

To conclude, the above illustrates how different spherical spaces influence CMB temperature fluctuations through their spectral properties and eigenmodes. However, some of the models discussed thus far assume a level of uniformity in the way spaces behave. In reality, some spherical manifolds are \emph{inhomogeneous} --- their CMB temperature distributions can depend on the observer's location. To account for this, we now examine \cite{Aurich_2011}, which analyses the effects of inhomogeneity on CMB radiation, focusing on how different observer positions within these spaces influence measured fluctuations.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -283,58 +323,65 @@ Furthermore, they excluded other groups such as the binary tetrahedral group $T^

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{CMB radiation in an inhomogeneous spherical space}

|

||||

In \cite{Aurich_2011}, the authors consider the CMB in spherical 3-manifolds that are inhomogeneous. Specifically, the space which we are working with is of the form $\mathbb S^3/\Gamma$, where $\Gamma$ is a group acting on $\mathbb S^3$ and the quotient is the set of orbits.

|

||||

In \cite{Aurich_2011}, the authors consider the CMB in spherical 3-manifolds that are \textit{multi-connected} and inhomogeneous, comparing them with their homogeneous counterparts. To start off, the manifolds used in the paper are all of the form $\mathbb S^3/\Gamma$, where $\Gamma$ is a group acting on $\mathbb S^3$, with the quotient being the set of orbits. The space being multi-connected means it is not simply connected, i.e. that not all loops are contractable to a point.

|

||||

|

||||

%This can also be seen as a covering, where $\S^3$ is the covering space, $\S^3/\Gamma$ is the space being covered, $\Gamma$ is the automorphism group and $\pi: x\mapsto \Gamma x$ is the covering map.

|

||||

The condition of the manifold being inhomogeneous means that, unlike the 3-sphere $\mathbb S^3$ and 3-torus $\mathbb T^3$, the manifold does not look the same at each point on the manifold. Because of inhomogeneity, the CMB is very much dependent on the point of observation.

|

||||

The condition of the manifold being inhomogeneous means that, unlike the 3-sphere $\mathbb S^3$ and 3-torus $\mathbb T^3$, the manifold does not look the same at each point on the manifold. We will define this properly later. Because of inhomogeneity, the CMB is very much dependent on the point of observation.

|

||||

|

||||

In the article, the authors discuss different spherical 3-manifolds, classifying whether they are inhomogeneous, analyzing their properties, and finding equivalences. For example, some of the manifolds in question are the lens manifolds $L(p,q)$ and the cubic manifolds $N2$ and $N3$.

|

||||

An important concept needed for formalizing this concept is that of the fundamental domain. Given the manifold $\mathbb S^3/\Gamma$, a fundamental domain is a subset of $\S^3$ which covers the entirety of $\S^3$ under the action of $\Gamma$. Moreover, all non-identity elements of $\Gamma$ must send elements in this set outside of it.

|

||||

|

||||

One important concept is the fundamental domain. Given our manifold $\mathbb S^3/\Gamma$, a fundamental domain is a subset of $\S^3$, which under the action of $\Gamma$ can reach the entirety of $\S^3$. Moreover, all non-identity elements of $\Gamma$ must send elements in this set outside of it. Intuitively, it is a set of representatives of $\S^3/\Gamma$ which are all next to one another, similarly to how $\Z/n\Z$ has $\{0,1,\dots,n-1\}$ as such a set. There is one specific fundamental domain that we care about, called the Voronoi domain. Given our observation point $x_0\in\S^3$, the Voronoi domain is the set of elements $x\in\S^3$ such that the following holds:

|

||||

Intuitively, one can imagine the manifold being covered by disjoint copies of the fundamental domain placed next to eachother, similarly to how $\mathbb{R}$ is tiled by the intervals $[n,n+1)$ for $n \in \mathbb{Z}$, forming a collection of such domains that cover the space under the standard action of $\mathbb{Z}$ on $\mathbb{R}$. Importantly, we are interested in one specific fundamental domain called the \emph{Voronoi domain}. Given an observation point $x_0\in\S^3$, the Voronoi domain is the set of elements $x\in\S^3$ such that

|

||||

$$ d(x_0,x) \leq d(x_0,g\cdot x) \quad \forall\, g\in\Gamma, $$

|

||||

where $d(\cdot,\cdot)$ is the $\S^3$-distance, analogous to the angular distance on $\mathbb{S}^2$. We define a manifold to be \emph{homogeneous} if the Voronoi domain is identical regardless of the observer $x_0\in\S^3$. Otherwise, the manifold is called \emph{inhomogeneous}.

|

||||

|

||||

$$ d(x_0,x) \leq d(x_0,g\cdot x) \quad \forall\, g\in\Gamma $$

|

||||

To determine whether a spherical manifold is homogeneous, one must understand the way group action changes with observer position. Changing the observer position is done mathematically by applying a change of coordinates $u'=uq$ with $u\in\S^3$ and $q$ an isometry in $\text{SU}(2,\mathbb C) \equiv \S^3$, making $u=q^{-1}$ the new origin $u'=q^{-1}q=e$. Then, using the general group element $g = (g_l,g_r)\in\Gamma$ and letting $\tilde u = g\cdot u = (g_l)^{-1}ug_r $, we get $ \tilde u' = (g_l)^{-1} u' (q^{-1}g_rq) $. The transformation in our shifted space is then $g' = (g_{l},q^{-1}g_{r}q)$, which generally differs from $g=(g_l,g_r)$. Therefore, if $g_r = q^{-1}g_rq$ does not hold for some $g$ and $q$ in the manifold, then the manifold is known to be inhomogeneous.

|

||||

|

||||

In the article, the authors discuss different spherical 3-manifolds, classifying whether they are inhomogeneous, analyzing their properties, and finding equivalences. Specifically, they look at manifolds of the form $\S^3/\Gamma$ with $\Gamma$ a group of order $8$, in order to make the volume equal to $2\pi^2/8$. Within those restrictions, we have the lens spaces $L(8,1)$ and $L(8,3)$, the cubic Platonic manifolds $N2$ and $N3$, and the manifold $D_8^*$ obtained when $\Gamma$ is the binary dihedral group. Analyzing said manifolds, one finds the equivalences $N2 \equiv L(8,3)$ and $N3\equiv D_8^*$. Furthermore, using the theory introduced previously, we learn that $N2$ is inhomogeneous while $N3$ and $L(8,1)$ are homogeneous.

|

||||

|

||||

\subsubsection{Results}

|

||||

|

||||

The rest of the article is about finding out how the CMB would look like in our three spaces $L(8,1)$, $L(8,3)\equiv N2$ and $N3$, with a focus on the difference between the homogeneous and inhomogeneous manifolds. For example, it finds that inhomogeneous spaces like $N2$ have a much higher variety of CMB anisotropies, because of how elements $g\in\Gamma$ act different depending on the observer. The main result is related to the suppression of CMB anisotropy over angles $60^\circ$ and larger. We see the strongest suppression in the Voronoi domains of $N2$ that are Platonic cube shaped. On the other hand, we see the least suppression in the lens shaped Voronoi domains of $N2$. Looking at $N3$ together with the total energy density parameter $\Omega_\text{tot}>1.07$, we notice an even larger suppression than for observers in $N2$.

|

||||

%this is just so that the change of section is not out of nowhere, put it at the end of what you are writting, it doesnt need to be in a dfferent subsection, however you should maybe do a small subsection of the main conslusion (like ariel and jus, with the subsections "silver lining" and "results"). if you do the small subsetion, put what i wrote in that section, perfect

|

||||

|

||||

Given the potential for anisotropies in spherical space models, it is crucial to test whether CMB fluctuations exhibit directional dependence. The study by \cite{Kashino_2012} develops a statistical framework for detecting anisotropies in the mean CMB temperature fluctuations. Their method employs spherical harmonic decomposition and Monte Carlo simulations to compare theoretical predictions with WMAP observational data.

|

||||

|

||||

where $d(\cdot,\cdot)$ is the $\S^3$-distance.

|

||||

|

||||

To figure out whether a spherical manifold is homogeneous, one must understand what the group action does under a change of observer position. Changing the observer position is done mathematically by applying a change of coordinates $u'=uq$ with $u\in\S^3$ and the isometry $q\in\text{SU}(2,\mathbb C) \equiv \S^3$, making $u=q^{-1}$ the new origin $u'=q^{-1}q=e$. Now, using the general group element $g = (g_l,g_r)\in\Gamma$ and letting $\tilde u = g\cdot u = (g_l)^{-1}ug_r $, we get $ \tilde u' = (g_l)^{-1} u' (q^{-1}g_rq) $. This means that the transformation in our shifted space is $g' = (g_{l},q^{-1}g_{r}q)$, which is not the same as $g=(g_l,g_r)$ in general. Therefore, if $g_r = q^{-1}g_rq$ does not hold for some $g,q$ in the manifold, it is inhomogeneous.

|

||||

|

||||

All of this can be used to figure out the observer-dependent CMB variations and other related values in different inhomogeneous spherical manifolds.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\subsection{Test for anisotropy in the mean of the CMB temperature fluctuation in spherical harmonic space}

|

||||

The temperature fluctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) provide crucial insights into the physics of the early universe and the underlying cosmological model.

|

||||

A fundamental assumption in standard cosmology ($\Lambda CDM$ model) is \textit{statistical isotropy}, meaning that the statistical properties of the CMB should be the same in all directions. Testing this assumption is essential, as deviations from isotropy could indicate alternative topologies for the universe.

|

||||

|

||||

From the point of view of Earth, we can view CMB as a function defined on the celestial sphere $\mathbb{S}^2$. Hence we can express CMB as the sum of spherical harmonics - a certain family of smooth functions defined on $\mathbb{S}^2$ which forms an orthonormal basis for $L^2(\mathbb{S}^2)$, meaning they are orthogonoal and of size 1, whith respect to the $L^2$ inner product.

|

||||

Following the article by \cite{Kashino_2012}, this section goes through an overview of a mathematical method for computing and interpreting CMB temperature fluctuations in spherical spaces, incorporating statistical isotropy, covariance structures, and Monte Carlo simulations, which are later compared with the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) seven-year observation data.

|

||||

|

||||

Following the article by Kashino et al. (2012), this section goes through an overview of a mathematical method for computing and interpreting CMB temperature fluctuations in spherical spaces, incorporating statistical isotropy, covariance structures, and Monte Carlo simulations, which are later compared with the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) seven-year observation data \cite{Kashino_2012}. \\

|

||||

The observed temperature fluctuations along a given direction on the celestial sphere can be expanded using spherical harmonics

|

||||

From the perspective of an Earth-based observer, we can view CMB as a function defined on the celestial sphere $\mathbb{S}^2$. Hence we can express CMB as the sum of spherical harmonics.\\

|

||||

The observed temperature fluctuations along a given direction in the celestial sphere can be expanded using spherical harmonics

|

||||

\[\Delta T(\hat{n}) = \sum_{\ell=0}^{\infty} \sum_{m=-\ell}^{\ell} a_{\ell m} Y_{\ell m}(\hat{n}),\]

|

||||

where $\Delta T(\hat{n})$ are fluctuations on the CMB temperature field, $Y_{\ell m}$ are the spherical harmonic functions evaluated in the direction of $\hat{n}$, and $a_{\ell m}$ are the spherical harmonic coefficients encoding temperature fluctuations at different scales. \\

|

||||

where $\Delta T(\hat{n})$ are fluctuations on the CMB temperature field in the direction of $\hat{n}$, $Y_{\ell m}$ are the spherical harmonic functions - which form an orthonormal basis for smooth functions on the sphere, and $a_{\ell m}$ are the \textit{spherical harmonic coefficients} (encoding temperature fluctuations at different angular scales). \\

|

||||

Under the assumption that the primordial fluctuations are statistically homogeneous and isotropic in the mean, and assuming they obey the Gaussian distribution, with the $2\ell+ 1$ spherical harmonic coefficients $a_{\ell m}$ for each $\ell$ being independent Gaussian variables, then the coefficients should satisfy the following condition:

|

||||

\[\langle a_{\ell m} \rangle = 0, \quad \langle a_{\ell m} a^*_{\ell' m'} \rangle = C_\ell \delta_{\ell \ell'} \delta_{m m'}\]

|

||||

\[\langle a_{\ell m} \rangle = 0, \quad \langle a_{\ell m} a^*_{\ell' m'} \rangle = C_\ell \delta_{\ell \ell'} \delta_{m m'}.\]

|

||||

Here $\langle ... \rangle$ denotes the average, $C_\ell$ is the ensemble average \textit{power spectrum}, which describes the variance of temperature fluctuations as a function of angular scale, and $\delta$ is the Kronecker delta. \\

|

||||

The condition $\langle a_{\ell m} \rangle = 0$ implies that the mean of the CMB temperature fluctuations should be zero when averaged over many realizations. Thus, if the mean is nonzero $\langle a_{\ell m} \rangle \neq 0$, it \textbf{suggests possible anisotropies or preferred directions in the universe} \cite{Kashino_2012}.

|

||||

|

||||

Here $\langle ... \rangle$ denotes the average, $C_\ell$ is the ensemble average power spectrum, which describes the variance of temperature fluctuations as a function of angular scale and $\delta$ is the Kronecker symbol. \\

|

||||

Thus, if the mean is nonzero $\langle a_{\ell m} \rangle \neq 0$, it \textbf{suggests possible anisotropies or preferred directions in the universe}.

|

||||

|

||||

Since real CMB observations are affected by instrumental noise and sky masking, estimating $C_\ell$ accurately requires simulations. Given a theoretical power spectrum $C^{th}_\ell$, the corresponding harmonic coefficients are drawn from a Gaussian distribution:

|

||||

Since real CMB observations are affected by instrumental noise and \textit{sky masking} (regions obscured by the Milky Way), estimating $C_\ell$ accurately requires simulations. To test for anisotropy, researchers compare the observed mean harmonic coefficients with theoretical predictions using Monte Carlo methods.

|

||||

Given a theoretical power spectrum $C^{th}_\ell$, used to generate synthetic realizations of the CMB sky, the corresponding harmonic coefficients are drawn from a Gaussian distribution:

|

||||

\[

|

||||

a_{\ell m} \sim \mathcal{N} (0, C_\ell^{\text{th}})

|

||||

a_{\ell m} \sim \mathcal{N} (0, C_\ell^{\text{th}}).

|

||||

\]

|

||||

|

||||

Applying a sky mask function $M(\hat{n})$ modifies the observed coefficients:

|

||||

|

||||

Applying a \textit{sky mask function} $M(\hat{n})$ modifies the observed coefficients:

|

||||

\[

|

||||

a^{\text{mask}}_{\ell m} = \sum_{\ell' m'} M_{\ell m, \ell' m'} a^{\text{all sky}}_{\ell' m'}

|

||||

a^{\text{mask}}_{\ell m} = \sum_{\ell' m'} M_{\ell m, \ell' m'} a^{\text{all sky}}_{\ell' m'},

|

||||

\]

|

||||

where $a^{\text{all sky}}$ represents the full-sky harmonic coefficients (which are unobtainable in practice), and $M_{\ell m, \ell' m'}$ is the convolution matrix of

|

||||

the mask, which accounts for mode coupling due to masking effects. However, this process introduces bias, which must be corrected using a decorrelation transformation based on the eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix.

|

||||

|

||||

where $a^{\text{all sky}}$ is taken from the all sky CMB map (which we can

|

||||

never obtain), and $M_{\ell m, \ell' m'}$ is the convolution matrix of

|

||||

the mask. This introduces mode coupling, which must be corrected using a decorrelation transformation based on the eigenvalue decomposition of the covariance matrix.

|

||||

Before we proceed, it is important that we introduce the concept of a \textit{multipole}, this corresponds to a mode in the spherical harmonic expansion of the CMB temperature fluctuations. Where each multipole represents a different angular scale in the sky. Moreover, we also have the the \textit{multipole moment} $\ell$, which corresponds to angular scales.

|

||||

|

||||

To test the assumption of statistical isotropy, we examine the mean of $a_{\ell m}$ across multipole bins. The test statistic is defined as:

|

||||

To test the assumption of statistical isotropy, we examine the mean of $a_{\ell m}$ across multipole ranges. The test statistic is defined as:

|

||||

\[

|

||||

S_i = \sum_{j} W_{ij} M_j

|

||||

S_i = \sum_{j} W_{ij} M_j,

|

||||

\]

|

||||

where $W$ is a decorrelation matrix derived from the covariance structure. If significant anomalies appear in the mean values of $a_{\ell m}$, this suggests deviations from isotropy that may indicate the need for new theories.

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

@ -381,27 +428,35 @@ If we try to look at deviations at both large and small scales simultaneously. I

|

|||

|

||||

The presence of an anomaly at $221 \leq \ell \leq 240$ suggests a possible connection to models of a finite curved universe. In a positively curved space (e.g., a three-sphere), allowed wave modes are quantized, which could lead to certain multipoles scales being preferred or suppressed in the CMB power spectrum.

|

||||

The results of this article, although not conclusive, support the idea that the universe (or at least the CMB sky) has a small preferred direction. Supporting the idea of a non-trivial topology in the universe, specifically a spherical one. Which is analyzed more into detail in the other articles discussed in the other sections.

|

||||

As a final note, the analysis is limited by the existing data for the CMB temperatures. Thus, future high-resolution independent CMB observations like PLANCK will further refine these methods, offering deeper insights into the fundamental nature of the universe and the topology of space-time.

|

||||

|

||||

As a final note, the analysis is limited by the existing data for the CMB temperatures. Thus, future high-resolution independent CMB observations like PLANCK will further refine these methods, offering deeper insights into the fundamental nature of the universe and the topology of space-time.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\section{Conclusion}

|

||||

%

|

||||

%\begin{figure}[H]

|

||||

% \centering

|

||||

% \includegraphics[width=0.25\linewidth]{binary-octahedron.png}

|

||||

% \caption{

|

||||

% In conclusion, the universe has a strange shape, and everything you knew is a lie. Fear the binary octahedral, for the end is near.}

|

||||

% \label{fig:binary-octahedron}

|

||||

%\end{figure}

|

||||

|

||||

\begin{figure}[H]

|

||||

\centering

|

||||

\includegraphics[width=0.25\linewidth]{binary-octahedron.png}

|

||||

\caption{

|

||||

In conclusion, the universe has a strange shape, and everything you knew is a lie. Fear the binary octahedral, for the end is near.}

|

||||

\label{fig:binary-octahedron}

|

||||

\end{figure}

|

||||

The study of CMB temperature fluctuations provides a means of establishing the geometry and topology of the universe. By analyzing key results from various studies, we discovered how different finite spherical topologies can constrain the possible allowed temperature fluctuations of the CMB, resulting in distinct theoretical predictions for the temperature anisotropies.

|

||||

|

||||

We took a detour into the realm of \emph{inverse spectral geometry and the Laplace-Beltrami operator}, and investigated isospectral pairs of spherical forms. Were any such pairs to exist, ambiguity in CMB analysis would become an issue, as our primary approach is analysis of the manifolds' spectrums. The silver lining is that all three-dimensional isospectral pairs of spherical spaces are also isometric, implying that determining the eigenmode spectrum is enough to determine the underlying topology for our spatial universe.

|

||||

|

||||

We then examined how different quotient spaces of the 3-sphere ($\mathbb{S}^3/\Gamma$), align with the CMB anisotropies. We found that certain spherical manifolds can lead to \textbf{suppressed large-scale CMB fluctuations}, potentially addressing anomalies observed in WMAP and Planck data. Moreover, the \textbf{binary octahedral and binary icosahedral} spaces have power spectra that align more closely with observed CMB anomalies, whereas other topologies (e.g., binary tetrahedral and cyclic groups) were found to be inconsistent with observations.

|

||||

We then examined the impact of \textbf{inhomogeneous spherical spaces}, where CMB temperature fluctuations may depend on the observer’s location. The study of \textbf{Voronoi domains} helps quantify the effects introduced by these spaces on the theoretical predictions of CMB anisotropies. Which is important to consider when comparing theoretical predictions in models of finite cosmic topology with observational data.\\

|

||||

Finally, we discussed statistical tests for \textbf{CMB isotropy}, focusing on the decomposition of temperature fluctuations into spherical harmonics. The power spectrum $C_\ell$ should be \textbf{statistically isotropic} in a homogeneous infinite universe, but anomalies in the \textbf{low multipole moments} ($221\leq \ell \leq 240$) \textbf{suggest possible deviations from isotropy}. By analyzing the test statistic $S_i$ across different frequency bands (Q, V, W from WMAP), we find that these anomalies persist even after accounting for instrumental noise, implying a possible \textbf{cosmological origin rather than observational artifacts}. Reinforcing the idea of the universe having a non-trivial cosmic topology, different from the one proposed by the $\Lambda$CDM model.

|

||||

|

||||

While no topology can be confirmed definitively, the mathematical and observational evidence discussed in this paper supports the idea that the universe may possess a non-trivial, multiconnected topology. Furthermore, finite spherical models remain viable candidates for explaining observed CMB anomalies. However, in order to reach a definitive answer, more precise CMB measurements and improved statistical analysis are required. Future CMB experiments, such as higher-resolution observations from Planck and next-generation satellite missions, along with further advancements in computational methods and theory, will be beneficial in testing these hypotheses more rigorously and improve our understanding of the topology of the universe. Further research could focus on developing statistical tests for CMB isotropy in an inhomogeneous universe. An important area for future research is the development of statistical tests for inhomogeneous spaces. Since, while significant progress has been made in analyzing homogeneous spherical manifolds, inhomogeneous spaces introduce observer-dependent effects that complicate standard isotropy tests.

|

||||

|

||||

We have designed and outlined a study of CMB temperature fluctuations in spherical spaces. We introduced spherical 3-manifolds as a plausible class of cosmological models and developed the mathematical tools (topology and eigenmode analysis) to handle them. Using these tools, we describe how one can compute CMB anisotropy patterns for a given spherical topology. We then connected these predictions to real data, discussing how one would recognize the fingerprint of a closed spherical universe in CMB observations ( such as through statistical anisotropies). Our synthesis of results from the articles by Aurich et al., Kashino et al., Pranav et al., and others shows that while no specific spherical topology is confirmed, the concept remains consistent with current data and even offers potential explanations for certain anomalies. It is relevant to mention that ongoing refinements in both theory and measurement could yet reveal a topological signature.

|

||||

%\printbibliography

|

||||

|

||||

%apalike-ejor IAS THE

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

\newpage

|

||||

|

||||

\bibliographystyle{plain}

|

||||

\bibliography{sources.bib}

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

|||

61

sources.bib

61

sources.bib

|

|

@ -111,51 +111,52 @@ Encryption Overview - Technical white paper}}, url={https://www.whatsapp.com/sec

|

|||

@book{Noone_2023, title={Banks are having a quantum computing revolution}, url={https://techmonitor.ai/hardware/quantum/who-are-early-adopters-quantum-computers-big-banks-finance}, publisher={Tech Monitor}, author={Noone, Greg}, year={2023}, month={}}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@book{aurich_2005, title={CMB anisotropy of spherical spaces}, url={https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0264-9381/22/17/006/pdf}, publisher={Classical and Quantum Gravity}, author={Aurich, Ralf and Lustig, Sven and Steiner, Frank}, year={2005}, month={}}

|

||||

@book{aurich_2005, title={CMB anisotropy of spherical spaces}, url={https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0264-9381/22/17/006/pdf}, publisher={Classical and Quantum Gravity}, author={Aurich, R. and Lustig, S. and Steiner, F.}, year={2005}, month={}}

|

||||

|

||||

@book{luminet_2005, title={Eigenmodes of three-dimensional spherical spaces and their application to cosmology}, url={https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/19/18/305}, publisher={Classical and Quantum Gravity}, author={ Lehoucq, Roland and Weeks, Jeffrey and Uzan, Jean-Philippe and Gausmann, Evelise and Luminet, Jean-Pierre}, year={2002}, month={}}

|

||||

@book{luminet_2005, title={Eigenmodes of three-dimensional spherical spaces and their application to cosmology}, url={https://doi.org/10.1088/0264-9381/19/18/305}, publisher={Classical and Quantum Gravity}, author={ Lehoucq, R. and Weeks, J. and Uzan, J. P. and Gausmann, E. and Luminet, J.P.}, year={2002}, month={}}

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@book{emilio, title={The spectral geometry of hyperbolic and spherical manifolds: analogies and open problems}, url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.10950}, publisher={who knows}, author={Emilio A. Lauret and Benjamin Linowitz}, year={2025}, month={}}

|

||||

@book{emilio, title={The spectral geometry of hyperbolic and spherical manifolds: analogies and open problems}, url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.10950}, publisher={New York Journal of Mathematics}, author={Lauret, E. A. and Linowitz, B. }, year={2025}, month={}}

|

||||

|

||||

@book{serri, title={Analysis on Manifolds}, url={https://github.com/mseri/AoM/releases}, publisher={AMS Open Math Notes}, author={Serri, Marcelo}, year={2025}, month={}}

|

||||

@book{serri, title={Analysis on Manifolds}, url={https://github.com/mseri/AoM/releases}, publisher={AMS Open Math Notes}, author={Serri, M.}, year={2025}, month={}}

|

||||

|

||||

@book{ikeda80, title={On the spectrum of a Riemannian manifold of positive constant curvature}, url={https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/repo/ouka/all/5171/}, publisher={ Osaka University and Osaka City University, Departments of Mathematics}, author={Ikeda, Akira}, year={1980}}

|

||||